By Dallas Rogers

*The Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University hosted the Australian premiere of the film Push at the Riverside Theatre on 18th October 2019 as a part of the Antenna Film Festival. The film was followed by a panel discussion chaired by Maryella Hatfield with panellists Dallas Rogers and Roderick Simpson.

The 2019 documentary film Push by Fredrik Gertten follows Leilani Farha, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, to a number of cities around the world as she tries “to understand who’s being pushed out of the city and why”[i]. It’s a film about housing, gentrification and finance. A Toronto real estate sales agent sets the scene in the open few minutes when he says, “So I got interested in real estate. Started with flipping properties: buying a house, renovating it and selling it. And I got the taste for real estate”[ii].

I was part of the panel for the Australian premiere of the film at the Antenna Film Festival on 18th October 2019 in Parramatta, Western Sydney*. The following is an edited version of my opening remarks from the panel discussion. The MC opened with an Acknowledgment of Country, as is common in Australia, and I also opened by acknowledging and paying respect to the Aboriginal people who have traversed and cared for the Burramatta[iii] lands for thousands of years.

Photo 1: Antenna Film Festival Panel discussion of Push; left to right, Dallas Rogers, Maryella Hatfield and Roderick Simpson.

Source: Juan Francisco Salazar

Aboriginal custodianship of land is a fitting starting point for a discussion about a film that resonates strongly with the housing problems in Sydney, because there can be no housing justice in Australia on stolen land. Land was one of the touchstones for our panel discussion, and we returned to the question of land several times. Saskia Sassen talks briefly about the importance of land in the film too, saying “Because of the massive buying of rural land more and more people have to leave the rural areas. They come to the cities. You can see that urban land become precious land.”[iv]

But the real achievement of this film is the way the film maker walks us through three key ways of thinking about housing: i) housing as a home; ii) housing as a commodity; and iii) housing as a financialised asset class[v].

Most of us live a house, and we’re intimately familiar with the idea of housing as a home. Home is a place you inhabit to satisfy some human need, and it can be a site of security and care. It’s often the building you live in, and we see this idea again and again in this film, and with a good degree of diversity. In fact, some of the most personal scenes in the film take place inside Leilani Farha’s home. We see Leilani dealing with piano practice and the challenges of parenting, including an amusing altercation over orange juice[vi].

Photo 2: Leilani Farha working from home.

Source: Push, documentary film at 7:10 minutes, WG Film AB, Sweden

I really like the way Fredrik Gertten uses Leilani and her family to set the baseline for the story – in these shots the most important thing about a house is that people live in them. With this baseline in place, Fredrik shifts onto another common, although slightly more abstract way of thinking about houses, and that is houses as commodities in a market of exchange. Put simply, this is how your home is produced by and functions within a housing market.

In Australia, after the Second World War housing was increasingly viewed as an instrument of capital accumulation – as a wealth producing asset. Today we hear about: ‘asset based welfare’, i.e., buying a house now and selling later to fund your retirement; or the ‘bank of mum and dad’, i.e., when parents give or lend their kids money to buy a house; or generation rent, i.e., the idea more and more people in Sydney are renting, and for longer. All of these are enabled by treating the house as a commodity in a housing market rather than, or as well as, a place to live.

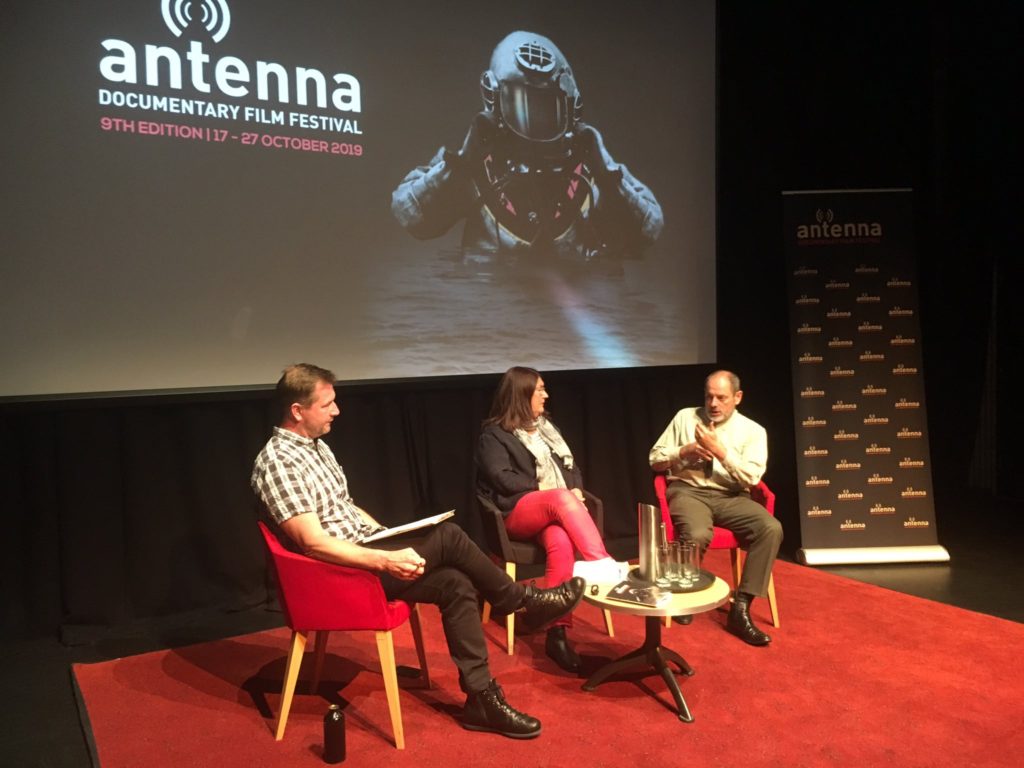

This is a strong theme in the film too, and like the repeated visual references to the housing as a home theme Fredrik returns to the home as a commodity theme again and again in the film. Fredrik takes us to London to hear about absent foreign real estate investors and their vacant properties[vii], and we hear about the negative impacts on local communities and businesses. This is reminiscent of Rowland Atkinson’s[viii] work in London I have written about before, where he shows how super-rich investors “create spaces of isolation, anonymity, exclusion and retreat” and develop “elaborate strategies to circumvent their entanglement with other social groups”.[ix]

Photo 3: Vacant London Property

Source: Push, documentary film at 15:55 minutes, WG Film AB Sweden

The research evidence looking at treating housing as a commodity in a market of exchange is clear; private housing markets are highly inequitable[x] and our current housing system rewards those who own one or more houses while penalising those who don’t.

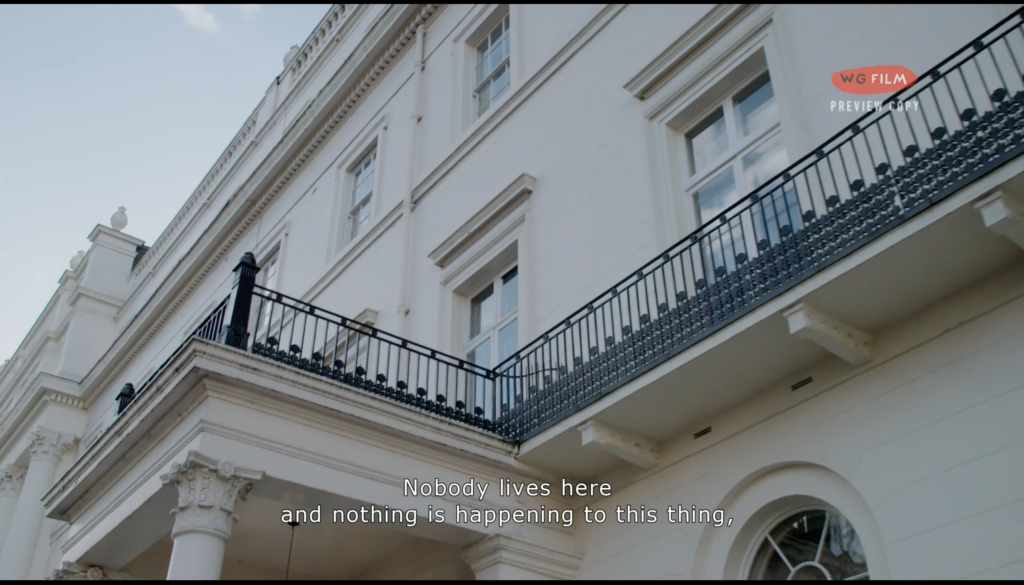

If you want to see the data on this, research by Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, Martijn Konings[xi] recently showed housing-based wealth is now a key determinate of inequality in Australia. They argue class in Australia is no longer determined by your job or wages, but rather by how many assets you have, with housing being key. In this asset-based society the winners and losers are determined by how many houses you own. We see this idea in the film too, with Leilani looking at a graph comparing median house price growth to stagnate wages.

Photo 4: Median house price growth compared to stagnate median hourly wages

Source: Push, documentary film at 7:20 minutes, WG Film AB, Sweden

I like the way Push puts the habitational and exchange value of housing into tension to tease out the implications of treating housing as a commodity rather than a home. But the film does more than this; it points towards where treating the home as a commodity is heading, and that’s housing as a financial asset class[xii].

Now treating the home as a metaphorical repository for storing and growing capital is abstract enough. But when we get to the financialisation of housing we get into really abstract territory. We become so detached from the home – so detached from the people who live in the home and from the building itself – that the bricks, mortar and people start to fade into the background, at least in the eyes of private equity fund managers.

Housing scholars[xiii] use the contested term ‘the financialisation of housing’ to talk about the penetration of abstract financial instruments into the housing system. And particularly their penetration into housing for the lower socio-economic groups such as the low income working poor or public housing tenants.

The classic and most well reported case of housing financialisation and its impacts is the 2007/8 global financial crisis, where fund managers, some thousands of miles away from the households who had been sold low-doc, sub-prime mortgages, were bundling these mortgages up and selling them off as securities around the world. As we now know, the sub-prime mortgage bust, which was partly underwritten by the financialisation of housing, sent shock waves through the global economy.

This is the real significance of the film Push; it takes a complex idea like the financialisation of housing and puts a human face to the trauma it produces while exposing how it works. It’s hard to get to the bottom of what the private equity fund managers are doing with our housing. There are complicated financial models, and shadowy banking practices, there’s shareholders and commercial-in-confidence, and all this keeps the financialisation of housing out of view.

What this film does is to push – pun intended – the financialisation of social housing into view, so we can see it for what it is. We can see who the key actors are, and what they’re doing, and how their abstract financial instruments work. We travel to Sweden where Stig Westerdahl[xiv] walks us around a social housing estate that has been acquired by Blackstone, trading as D.Carnegie in Uppsala. Stig talks about rents increasing by up to 50% and tenant services decreasing on the estate. Then we shift to Joseph Stiglitz, who unpacks the financial logic of Blackstone by saying;

“They don’t really want to tie up all their money into these houses. So what they do is look for a large number of investors. And they create a security – a tradable financial asset – that says we own these 10,000 homes [a]nd you, as the investor, will get the rents and any capital gains on those properties. And if you buy 1% of the security, you get 1% of that flow. That means Blackstone doesn’t have its own money at risk to the same extent as it otherwise would be”[xv].

Then we learn about Blackstone’s private equity model from one of its architects, Jonathan Gray, Blackstone’s Global Head of Real Estate. When asked, “So, one of the markets you went into was single-family homes, and you have a big portfolio… Tell us about that. So how do you even find 50,000 homes to buy?”, Jonathan responds, “You need a global financial crisis for that to occur. You’re sitting around in 2011, saying ‘where is there a large pool of assets that are going to be sold by financial institutions at big discounts to underlying replacements costs?”.

Photo 5: Jonathan Gray, Blackstone’s Global Head of Real Estate

Source: Push, documentary film at 38:30 minutes, WG Film AB, Sweden

At this moment, the financialisation of housing is brought clearly into view. Saskia Sassen reminds us in the film that companies like Blackstone don’t want us to see the inner workings of their businesses. It is clear these private equity business models are predatory, and the private equity firms would prefer it if we were kept in the dark. They like us to think their financial instruments and systems are too complicated for us to understand.

At this point the film also starts to drift away from the financialisation of housing story and onto city and metropolitan government organising at the global scale as a possible solution to ‘the push’[xvi]. But Fredrik runs a cat and mouse story arc from midway through the film, with Leilani trying to get Blackstone into a room to talk through the ethics of their business model; and alas, in the closing quarter of the film Blackstone cancel their meeting with Leilani. So rather than ending on the housing as a financialised asset class theme Fredrik returns to the Toronto real estate sales agent who opened the film and therefore symbolically ends the film by returning to housing as a commodity.

Photo 6: Blackstone cancel their meeting with the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing

Source: Push, documentary film at 1:00:35 minutes, WG Film AB, Sweden

The academic in me really wanted the story arc of the film to begin with contrasting housing as a home and housing as commodity, and to finish with housing as a financialised asset class. I would have liked to hear Desiree Fields talk about the private equity housing model and its impact on people in the US. Desiree’s work shows[xvii] the financialisation of housing is about more than the problems with our private housing markets; there is something more sinister at play[xviii]. But the radio maker in me knows this is not how documentary storyboarding and expert video grabs work, and I have to admit the real power of the film is the way it brings this private equity housing model into the mainstream without too much academic hyperbole.

I really enjoyed this film and Leilani is particularly powerful. So, it’s a big thumbs up from me; and there are four key observations we can take from the film into our discussions about housing in Sydney and Australia.

First, there can be no housing justice on stolen land, and we must reconcile with our past and develop new ways of thinking about, and using, land. This of course means attending to questions about Aboriginal land dispossession, but it also means thinking about how we use public land for housing in Sydney. I’m on the record[xix], along with more than half a dozen of Sydney’s leading housing researchers, calling for at least 30% of all new housing developments on publicly owned land to be ‘affordable’. Affordability, by the way, should be determined by income rather than, say, 20% under market-based rent.

Second, we need to revalue housing as a home. Revalue the ‘use value’ or the habitational function of the home. This is exactly what the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, Leilani Farha, is doing with the #Right2Housing and #MaketheShift campaigns. So, look these campaigns up and get onboard.

Photo 7: UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing’s #Right2Housing campaign

Source: Author, from Twitter

Third, we need to continue to challenge the idea that the private housing market is the only or best way to provide housing in our cities. There are other ways of providing housing that can run alongside the private housing market. If you want a good example look up Louise Crabtree and Jason Twill’s land and housing affordability work with the City of Sydney. They’re proposing a City of Sydney area-wide community land trust policy and development model that “would enable not-for-profit, community-based organizations to hold land titles for perpetual affordability and remove land costs from housing development”[xx].

Finally, we need to be on high alert for the signs of the financialisation of housing in Australia. The film does a good job of exposing the private equity housing model, and it is signs of this ‘business model’ rather than the entry of a particular global business per se we need to look out for in Australia. We need to unmask the abstract financial instruments of companies like Blackstone before they hit our shores.

_____________

[i] See: http://www.pushthefilm.com/

[ii] Push, documentary film, WG Film AB, Sweden (at 2:45 minutes)

[iii] Burramatta is the Aboriginal name for Parramatta, which translates as the place where the eels lie down.

[iv] Push, documentary film, WG Film AB, Sweden (at 13:13 minutes)

[v] For a good summary of these ideas see: Madden, D. and P. Marcuse (2016) In defense of housing: the politics of crisis. Verso Books, London.

[vi] Push, documentary film, WG Film AB, Sweden (at 7:10 minutes)

[vii] Atkinson, R. (2019). Necrotecture: Lifeless Dwellings and London’s Super‐Rich. International Journal of Urban Regional and Research.

[viii] Atkinson, R. (2016). Limited exposure: Social concealment, mobility and engagement with public space by the super-rich in London. Environment and Planning A.

[ix] Rogers, D., & Koh, S.Y. (2017) The globalisation of real estate: the politics and practice of foreign real estate investment. International Journal of Housing Policy.

[x] Madden, D. and P. Marcuse (2016) In defense of housing: the politics of crisis. Verso Books, London.

[xi] Adkins, L., Cooper, M., & Konings, M. (2019). Class in the 21st century: Asset inflation and the new logic of inequality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space.

[xii] Fields (2018) Constructing a New Asset Class: Property-led Financial Accumulation after the Crisis. Economic Geography, 94:2, 118-140.

[xiii] Jacobs, J., & Manzi, T. (2019) Conceptualising ‘financialisation’: governance, organisational behaviour and social interaction in UK housing.International Journal of Housing Policy.

[xiv] Push, documentary film, WG Film AB, Sweden (at 30:45 minutes)

[xv] Push, documentary film, WG Film AB, Sweden (at 31:35 minutes)

[xvi] This is a key aspect if the film, which I have not discussed here.

[xvii] Fields (2018) Constructing a New Asset Class: Property-led Financial Accumulation after the Crisis. Economic Geography, 94:2, 118-140.

[xviii] Fields, D. (2019). Automated landlord: Digital technologies and post-crisis financial accumulation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space.

[xix] See: https://theconversation.com/sydney-needs-higher-affordable-housing-targets-69207

[xx] See: https://architectureau.com/articles/seven-entries-shortlisted-in-city-of-sydneys-alternative-housing-ideas-competition/